A History of Struggle

FAMOUS LABOR STRIKES

Haymarket Massacre | Bread & Roses Strike | Ludlow Massacre | West Coast Waterfront Strike | Longshore Strike

Chicago’s 1886 Haymarket Massacre

The Haymarket affair (also known as the Haymarket massacre or Haymarket riot) was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on Tuesday May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago. It began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour day and in reaction to the killing of several workers the previous day by the police. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at police as they acted to disperse the public meeting. The bomb blast and ensuing gunfire resulted in the deaths of seven police officers and at least four civilians; scores of others were wounded.

In the internationally publicized legal proceedings that followed, eight anarchists were convicted of conspiracy. The evidence was that one of the defendants may have built the bomb, but none of those on trial had thrown it. Seven were sentenced to death and one to a term of 15 years in prison. The death sentences of two of the defendants were commuted by Illinois governor Richard J. Oglesby to terms of life in prison, and another committed suicide in jail rather than face the gallows. The other four were hanged on November 11, 1887. In 1893, Illinois’ new governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the remaining defendants and criticized the trial.

The Haymarket Affair is generally considered significant as the origin of international May Day observances for workers. The site of the incident was designated a Chicago Landmark in 1992, and a public sculpture was dedicated there in 2004. In addition, the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument at the defendants’ burial site in nearby Forest Park was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997.

“No single event has influenced the history of labor in Illinois, the United States, and even the world, more than the Chicago Haymarket Affair. It began with a rally on May 4, 1886, but the consequences are still being felt today. Although the rally is included in American history textbooks, very few present the event accurately or point out its significance,” according to labor studies professor William J. Adelman.

During the economic slowdown between 1882 and 1886, socialist and anarchist organizations were active. Other anarchists operated a militant revolutionary force with an armed section that was equipped with guns and explosives. Its revolutionary strategy centered around the belief that successful operations against the police and the seizure of major industrial centers would result in massive public support by workers, start a revolution, destroy capitalism, and establish a socialist economy.

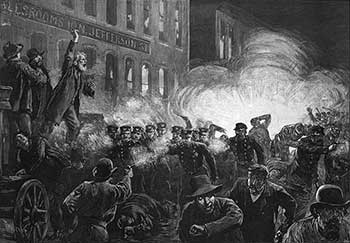

This 1886 engraving was the most widely reproduced image of the Haymarket Affair. It inaccurately shows Fielden speaking, the bomb exploding, and the rioting beginning simultaneously.

This 1886 engraving was the most widely reproduced image of the Haymarket Affair. It inaccurately shows Fielden speaking, the bomb exploding, and the rioting beginning simultaneously.

Click HERE to View the Complete Article

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bread and Roses Strike of 1912

Massachusetts militiamen with fixed bayonets surround a group of peaceful strikers

Massachusetts militiamen with fixed bayonets surround a group of peaceful strikers

The Lawrence textile strike (Bread and Roses Strike) was a strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Prompted by a two-hour pay cut corresponding to a new law shortening the workweek, the strike spread rapidly through the town, growing to more than twenty thousand workers and involving nearly every mill in Lawrence.

The strike united workers from more than 40 different nationalities. Carried on throughout a brutally cold winter, the strike lasted more than two months, defying the assumptions of conservative trade unions within the American Federation of Labor (AFL) that immigrant, largely female and ethnically divided workers could not be organized. In late January, when a striker, Anna LoPizzo, was killed by police during a protest, IWW organizers Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti were arrested on charges of being accessories to the murder.

IWW leaders Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn came to Lawrence to run the strike. Together they masterminded its signature move, sending hundreds of the strikers’ hungry children to sympathetic families in New York, New Jersey, and Vermont. The move drew widespread sympathy, especially after police stopped a further exodus, leading to violence at the Lawrence train station. Congressional hearings followed, resulting in exposure of shocking conditions in the Lawrence mills and calls for investigation of the “wool trust.” Mill owners soon decided to settle the strike, giving workers in Lawrence and throughout New England raises of up to 20 percent. Within a year, however, the IWW had largely collapsed in Lawrence.

The Lawrence strike is often referred to as the “Bread and Roses” strike. It has also been called the “strike for three loaves”. The phrase “bread and roses” actually preceded the strike, appearing in a poem by James Oppenheim published in The Atlantic Monthly in December 1911. A 1916 labor anthology, The Cry for Justice: An Anthology of the Literature of Social Protest by Upton Sinclair, attributed the phrase to the Lawrence strike, and the association stuck. “Bread and roses” has also been attributed to socialist union organizer Rose Schneiderman.

The tactic of sending children of textile workers to live with supporters in New York City reduced maintenance costs of the strikers and generated public sympathy and financial support.

The tactic of sending children of textile workers to live with supporters in New York City reduced maintenance costs of the strikers and generated public sympathy and financial support.

Click HERE to View the Complete Article

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1914 Ludlow Massacre

Ludlow Monument was erected by the United Mine Workers of America.

Photo Credit: Flickr

The Ludlow Massacre was an attack by the Colorado National Guard and Colorado Fuel & Iron Company camp guards on a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal miners and their families at Ludlow, Colorado, on April 20, 1914. About two dozen people, including miners’ wives and children, were killed. The chief owner of the mine, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. , was widely criticized for the incident.

The massacre, the seminal event in the Colorado Coalfield War, resulted in the violent deaths of between 19 and 26 people; reported death tolls vary but include two women and eleven children, asphyxiated and burned to death under a single tent. The deaths occurred after a daylong fight between militia and camp guards against striking workers. Ludlow was the deadliest single incident in the southern Colorado Coal Strike, which lasted from September 1913 through December 1914. The strike was organized by the United Mine Workers of America against coal mining companies in Colorado. The three largest companies involved were the Rockefeller family -owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, and the Victor-American Fuel Company.

In retaliation for Ludlow, the miners armed themselves and attacked dozens of mines over the next ten days, destroying property and engaging in several skirmishes with the Colorado National Guard along a 40-mile front from Trinidad to Walsenburg . The entire strike would cost between 69 and 199 lives. Thomas G. Andrews described it as the “deadliest strike in the history of the United States,” commonly referred to as the Colorado Coalfield War.

The Ludlow site, 18 miles northwest of Trinidad, Colorado , is now a ghost town. The massacre site is owned by the United Mine Workers of America, which erected a granite monument in memory of the miners and their families who died that day. The Ludlow Tent Colony Site was designated a National Historic Landmark on January 16, 2009, and dedicated on June 28, 2009. Modern archeological investigation largely supports the strikers’ reports of the event.

Ruins of Ludlow

Ruins of Ludlow

Click HERE to View the Complete Article

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Great Waterfront Strike of 1934

Waterfront strike scenes, 1934, silent footage.

Video Credit: Prelinger Archive

The 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike (also known as the 1934 West Coast Longshoremen’s Strike, as well as a number of variations on these names) lasted eighty-three days, triggered by sailors and a four-day general strike in San Francisco, and led to the unionization of all of the West Coast ports of the United States.

The San Francisco General Strike, along with the 1934 Toledo Auto-Lite Strike led by the American Workers Party and the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike of 1934 led by the Communist League of America, were important catalysts for the rise of industrial unionism in the 1930s, much of which was organized through the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

The strike began on May 9, 1934, as longshoremen in every West Coast port walked out; sailors joined them several days later. The employers recruited strikebreakers , housing them on moored ships or in walled compounds and bringing them to and from work under police protection. Strikers attacked the stockade housing strikebreakers in San Pedro on May 15; two strikers were shot and killed by the employers’ private guards. Similar battles broke out in San Francisco and Oakland, California, Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington. Strikers also succeeded in slowing down or stopping the movement of goods by rail out of the ports.

The Roosevelt administration tried again to broker a deal to end the strike, but the membership twice rejected the agreements their leadership brought to them. The employers then decided to make a show of force to reopen the port in San Francisco. On Tuesday, July 3, fights broke out along the Embarcadero in San Francisco between police and strikers while a handful of trucks driven by young businessmen made it through the picket line.

Some Teamsters supported the strikers by refusing to handle “hot cargo” – goods which had been unloaded by strikebreakers, although the Teamsters’ leadership was not as supportive. By the end of May , Dave Beck, president of the Seattle Teamsters, and Mike Casey, president of those in San Francisco, thought the maritime strike had lasted too long. They encouraged the strikers to take what they could get from the employers and threatened to use Teamsters as strikebreakers if the ILA didn’t return to work.

The Great Waterfront Strike of 1934

The Great Waterfront Strike of 1934

Click HERE to View the Complete Article

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Longshore Strike of 1948

The Longshore Strike 1948 was an industrial dispute which took place in 1948 on the west coast of the United States. President of the ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union) at the time was Harry Bridges . The WEA (waterfront employers association) led by Frank P. Foise were in a conflict, they were unable to come to agreeable terms and with the issues of hiring and the politics of union leadership, longshoremen and marine unions performed a walk out on September 2, 1948.

The strike shut down the United States’ West Coast ports and put a dent in American labor history and a positive change for future longshoremen.

Click HERE to View the Complete Article

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“The People United Will Never Be Defeated”

SR Holguin, PC has extensive experience providing full-service legal representation to private and public sector unions, and multi-employer trust funds.